I realize that sporting events such as international cricket matches and World Boxing Championships are entertaining because they are exciting, tribal, channels of aggression and adrenaline, etc., and I do not begrudge those who seem to find unending delight in watching these events and cheering for their favorite teams.

However, what I do find quite amusing is the "analysis" of a win or a loss in terms of statistics, "weather conditions", "team morale". As a typical example of this ludicrous post-facto wisdom, read this. (notice the word which is part of the URL).

In short, teams lose because they do not perform well (!). That otherwise intelligent people fall for such analyses simply boggles the mind.

Monday, November 09, 2009

The Pacifist and the Warlord

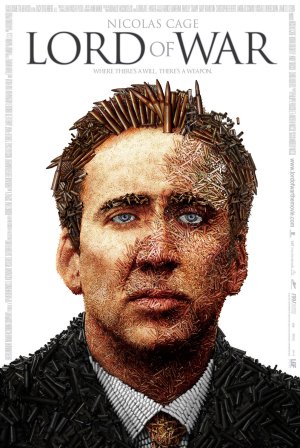

- Lord of War (Andrew Niccol, 2005): Nicolas Cage acts as an illegal gunrunner, and this film is a nihilistic look at humans' propensity for violence. Not at all preachy, dripping with irony and black humour (some of which may be found repulsive by compassionate souls), and with some stunning cinematography, the film is not a glorification of Mr Cage's character, but is rather a perplexing treatise on harm and malice. The gunrunner is not malicious at all, but he is engaged in helping others carry out their malice. "I don't want people dead, Agent Valentine. I don't put a gun to anybody's head and make them shoot. But shooting is better for business. But, I prefer people to fire my guns and miss." And further, in a wry moment, he remarks: "They say 'Evil prevails when good men fail to act.' What they ought to say is, 'Evil prevails.'"

- The Mission (Roland Joffé, 1986): A completely different kind of film from the above: serious, sincere, poetic, a polemic against violence. Father Gabriel (Jeremy Irons, in a standout performance) is a Jesuit priest in opposition to the colonial powers in 18th century South America. He refuses to resist the violent aggressors, and leads his mission to martyrdom. One wonders at the end if his attachment to pacifism was also in part responsible for the horrific violence to the people under his leadership. One also wonders if peace and love can ever be taught without recourse to divinity. Very often, the religious claptrap is justified because it serves ostensibly noble ends. The film is rightly cherished for its great scenery and lilting music and won the Golden Palm at Cannes. (And it is rather peculiar that a film about the horrors of violent aggression shows a warrior on its poster, rather than, say, a face expressing love and kindness)

Tuesday, November 03, 2009

Antichrist by Lars von Trier

A film not for the faint of heart, or for the weak of mind for that matter (I plead guilty to the charge of Elitism). The film is not just extremely violent, it also raises serious questions about the war of the sexes, about rationality versus nature debate, about religion, and about the nurture instinct versus the desire instinct.

Starting almost operatically, with a very high degree of cinematic control, the film plunges slowly, chapter by chapter, into the dark recesses and chaos of a woman's uncontrollable nature.

There are distinct (if inadvertent) echoes of Irreversible (Gaspar Noe, 2002), especially as it explores the issue of whether female nature inspires violence (in both films, the woman is subjected to horrific violence), the nature of desire and domination (in both films, the woman is a very wilful character till the very end who dominates the man/men emotionally till she is avenged physically by mankind), the drives of sadism (in both films, hurtful violence is part of sexuality), grief and madness, and the treatment of woman as nature (in both films, there is a spectacular shot of the woman being an inseparable part of the green of nature).

I think the film raises serious issues, but I also appreciate Mike D'Angelo when he writes in his open letter to von Trier:

Nature is not just the trees and the birds, it is also our own impulses and passions. The force of passions scare Her, and (in the pyramid of her fears) her deepest fear is therefore depicted as that of Her own Self. I have to say that I was bemused by the overt symbolism of bondage (a round stone, no less, tied (sic) to the man's leg by the woman). For those who want to explore the nature of self-injury as a form of revenge against one's own sexuality, and who (WARNING) do not flinch easily, I recommend Cutting Moments (Douglas Buck, 1997), a rather disturbing short film.

I find the following comment on IMDB to be very insightful about this film (Warning: SPOILERS):

Starting almost operatically, with a very high degree of cinematic control, the film plunges slowly, chapter by chapter, into the dark recesses and chaos of a woman's uncontrollable nature.

There are distinct (if inadvertent) echoes of Irreversible (Gaspar Noe, 2002), especially as it explores the issue of whether female nature inspires violence (in both films, the woman is subjected to horrific violence), the nature of desire and domination (in both films, the woman is a very wilful character till the very end who dominates the man/men emotionally till she is avenged physically by mankind), the drives of sadism (in both films, hurtful violence is part of sexuality), grief and madness, and the treatment of woman as nature (in both films, there is a spectacular shot of the woman being an inseparable part of the green of nature).

I think the film raises serious issues, but I also appreciate Mike D'Angelo when he writes in his open letter to von Trier:

I think you’re in deadly earnest about the nature of grief and its relation to madness. And yet you take it so far over the top, in so many different ways, that it’s almost impossible not to laugh.To be fair to von Trier and to the film, I didn't laugh even once. I found the film quite somber and meaningful, but I do agree that some of the scenes might be too much for a normal viewer. von Trier strays as far from his Dogme-95 manifesto as possible: using slow motion, tricks of lighting, rotoscoping, special effects, background music, ... What hasn't changed is the extreme demands he places on his actors. The performance by Charlotte Gainsbourg stands out in my limited film experience as one of the finest and most harrowing performances by an actress. Her final scene with her husband is nothing short of extraordinary.

Nature is not just the trees and the birds, it is also our own impulses and passions. The force of passions scare Her, and (in the pyramid of her fears) her deepest fear is therefore depicted as that of Her own Self. I have to say that I was bemused by the overt symbolism of bondage (a round stone, no less, tied (sic) to the man's leg by the woman). For those who want to explore the nature of self-injury as a form of revenge against one's own sexuality, and who (WARNING) do not flinch easily, I recommend Cutting Moments (Douglas Buck, 1997), a rather disturbing short film.

I find the following comment on IMDB to be very insightful about this film (Warning: SPOILERS):

In the film, “She” — the name of Gainsborg’s character — had been writing a thesis on violence against women through history. She realized that “nature … causes people to do evil things to women,” but concluded that female nature is also part of this cycle; the nature of women inspires violence. As She explains it, women lack complete control over their own bodies, which are animated by satanic spirit.

For her, images such as those she collects of early modern witches copulating with demons, capture an essential truth. Her therapist husband, whose relentless rationalism fails to cure her, resists the inevitability of this truth until the very end.

Gainsbourg’s character, through her sexual frenzies and shifts of mood, seems connected to the natural world of Eden around her. When she observes that “Nature is Satan’s church,” it is not difficult to infer that while Christ was half man, half divine, Antichrist is half woman, half Satanic. Indeed, She does not seem completely in control of herself. Fearing his abandonment, She suddenly brutalizes her husband's genitalia by smashing it with a huge log of wood. Then she just as suddenly switches back to nurturing mode, by her sudden frenzied manual stimulation of his traumatized penis to orgasm. In her brutalizing mode, for example, She bolts a grindstone to his leg, and then throws the wrench under the house to prevent an escape. Later, in her nurturing mode, She wants to remove the grindstone and help her husband back to the house; She looks for the wrench in the toolbox as if she were not aware that she herself had hidden it elsewhere.

Such splitting of her personality recurs. In one (notorious) sequence, She remembers watching her child fall from the window while she did nothing to stop him because she was caught up in sexual ecstasy. When, horrified at her own conduct, She performs a genital self-mutilation, she is trying to protect herself as well as others from this uncontrollable destructive force within herself.

The fact that She herself is horrified by female sexual power seems to undermine any notion that what the film depicts is a result of patriarchal oppression. Rather, it is hard to escape the conclusion that She has rediscovered the truth that He, in his rationalistic naivete, has dismissed out of hand. And their own and the world's

expulsion from Eden — the corruption of the world — was not simply the Fall of Man but the Rise of Woman.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)