25th Hour (Spike Lee, 2002) and The Wrestler (Darren Aronofsky, 2008) both take an utterly humane look at a man nearing the end of his life as he knows it. The protagonist in both the films is the kind of man people love to hate and revile, pour scorn on, and otherwise consider the scum of the earth.

Where the Spike Lee film is about the last day before a drug dealer in New York goes to jail, the Aronofsky film is about a showbiz wrestler (one of those who fight choreographed and fake battles in the ring with dialogue and spectacle). Both films are remarkable in that they succeed in humanizing and bringing depth to the kind of person who are generally considered to only have a shallow, dark side.

In 25th Hour, the director juxtaposes the drug dealer's life with his other so-called normal friends (who don't pay the price of their mistakes, whereas he does). This film does not say anything overtly, is more subtle in what it wants to show us. Many critics have justly admired the two amazing stream of consciousness scenes in this film (the first in the protagonist's mind as he pours out his contempt for others as a means of validating himself, and the second in his father's mind as he pours out his fatherly fantasy of letting his son escape the law). Both are poignant in their own way, the second much more because its canvas is far more extended.

In The Wrestler, the director illustrates not just the inner life of the wrestler himself, but also the inner life of a lap dancing woman. It is obvious to see the connection. Both are subjecting their body to a voyeuristic and superficially entertaining abuse in order to make their living. But the similarity ends there. The woman knows that hers is a false life but the wrestler, unable to find any succour in his actual relationships, turns, tragically, back to the ring in order to find meaning and sympathy. In one of the most devastating scenes in recent films, he fights his final battle with a man who, while beating him and taking a beating from him, shows great empathy and understanding towards him during the fight. I mean, who could have thought that these muscle-bound neanderthals could have such depth of character, and while fighting?

Man is complex, and his motivations are complicated. To see a man as evil just because he made a socially reprehensible choice, or because he slipped somewhere where most people don't, is to ignore his vastness, his essential similarity with the rest of us.

And of course, Mickey Rourke and Edward Norton are a pleasure to watch in their performances in the respective films.

Monday, December 28, 2009

Wednesday, December 23, 2009

Food for Thought, and for the Soul

Pleasurable Consumption is a very vast subject. Once the survival needs of the body are taken care of, what do you look forward to?

Most people then move on to seeking pleasure.

It is not necessary to define pleasure, except to note that certain neurobiological processes are involved.

Cognitive pleasures and affective pleasures are usually interpretative and imaginative in nature. These armchair-pleasures, as it were (e.g. Watching television, communicating over email or over the phone, computer games, listening to music, reading, surfing the internet, indulging in virtual social networking), are to create an imaginative world in the mind, in which narcissism regins supreme. I am the king (or queen) in these virtual worlds.

These pleasures provide the illusion of being connected, while one is increasingly isolated and alone.

This illusion and sense of self-importance needs to be sustained and nurtured by repeated affirmations, hence the addiction to these pleasures, which addiction is reaching epidemic proportion in urban affluent classes.

What, for example, is the essential reason of posting something on Facebook for most people? It is to seek acknowledgment of one's existence, an affirmation of one's tastes, a sense of sharing the intimate details of one's life in an increasingly crowded but lonely world.

And is it not true, that if nobody responds to your posts, nobody replies to your emails, and nobody comments on your status updates, you get depressed?

We are moving from sharing of experiences in the real world (conversations, walks, eating together, singing and dancing, playing together) to sharing in the virtual world (people doing all these, except dancing perhaps, while being physically isolated).

The need to belong, to connect, remains, but given the constraints of modern living, the easiest way in which to fulfill this need is via the global telecommunications network.

Many decry this change, many herald this change.

Just like in a pornographic film, in which the lovers simply and without much of a prelude and fuss engage in sex, digital pleasures are cutting to the chase and addressing the pleasure center without addressing the physical body.

The time is not far when even the eyes and hands (the screen and the keyboard) will be unnecessary. Direct control of the computer from the brain, and direct feedback to the brain. Further down, I speculate that the feedback may even stimulate the sensory centers, to the extent of providing a full sensual experience, completely virtually.

In this paradigm, the body is seen only as a vehicle of geting pleasure, and if pleasure can be directly and instantly delivered to the brain, why bother with physical acts? Why bother getting up from the couch?

More and more, I think, we will see pleasures (and ads, which support them) being more precisely targeted.

Physical health is obviously going to suffer, but are there any other consequences?

I think, firstly, digital entertainment is going to result in intellectual devolution for a vast majority of people. Some will use the new tools to further their understanding, but most will use these to augment their existing biases.

Digital entertainment puts one in control. Whether it be a click of the mouse, or pressing a button to change a channel on the TV, one is enabled to be more and more impatient, selective, and intolerant. Since now one has the power to not perceive what one does not want to, what happens to intellectual growth? There is no incentive (or lack of choice) to watch something which one may not agree with. And disagreement, criticism of one's ideas, and dialectical engagement is the essential ingredient of intellectual growth.

Secondly, facts take a backseat, and perceptions and impressions and opinions become primary. After all, if one's primary interface to the world is through a screen, what is the difference between a war shown in a movie, and a war shown as a news item?

Thirdly, the democratic process is undermined. What is the value of an opinion, if it is based on what you have been told? Driven by what is most visible in the digital world (controlled by media houses), and given that it is too much effort to find out what is really true in a flood of information, most people are going to end up believing what big media needs them to believe.

Fourthly, actual relationships (if any) will get burdened from the stress of conforming to virtual idealizations. What was earlier a teenage fantasy (the Mills and Boon romances) is now an adult expectation, due to the larger and larger role media and its depictions of relationships (and physical beauty, and sex) are playing in our lives.

There are many more consequences, but these derive from the above.

...

Do you have a choice of disengaging from the virtual/digital world and still not feel lonely, isolated, without anyone to share your experiences with? What if most of your relatives, friends, colleagues are deep in the "matrix"? Will you be able to coax them out? Isn't it true that these days, people resent you if you take them away from their phone, computer or television? What will you do without using the very tools of communication that others are hooked on to?

It is a tough problem, and is going to become much tougher. What are your thoughts on this new world, where with your minds and souls being nourished through wires, your body is only useful as a provider of blood sugar to your brain?

Is the day far when education will be primarily how to learn to use a computer, work will be primarily how to instruct a computer and to create digital content, and entertainment will be primarily hooking on to the computer?

Look around.

Most people then move on to seeking pleasure.

It is not necessary to define pleasure, except to note that certain neurobiological processes are involved.

Cognitive pleasures and affective pleasures are usually interpretative and imaginative in nature. These armchair-pleasures, as it were (e.g. Watching television, communicating over email or over the phone, computer games, listening to music, reading, surfing the internet, indulging in virtual social networking), are to create an imaginative world in the mind, in which narcissism regins supreme. I am the king (or queen) in these virtual worlds.

These pleasures provide the illusion of being connected, while one is increasingly isolated and alone.

This illusion and sense of self-importance needs to be sustained and nurtured by repeated affirmations, hence the addiction to these pleasures, which addiction is reaching epidemic proportion in urban affluent classes.

What, for example, is the essential reason of posting something on Facebook for most people? It is to seek acknowledgment of one's existence, an affirmation of one's tastes, a sense of sharing the intimate details of one's life in an increasingly crowded but lonely world.

And is it not true, that if nobody responds to your posts, nobody replies to your emails, and nobody comments on your status updates, you get depressed?

We are moving from sharing of experiences in the real world (conversations, walks, eating together, singing and dancing, playing together) to sharing in the virtual world (people doing all these, except dancing perhaps, while being physically isolated).

The need to belong, to connect, remains, but given the constraints of modern living, the easiest way in which to fulfill this need is via the global telecommunications network.

Many decry this change, many herald this change.

Just like in a pornographic film, in which the lovers simply and without much of a prelude and fuss engage in sex, digital pleasures are cutting to the chase and addressing the pleasure center without addressing the physical body.

The time is not far when even the eyes and hands (the screen and the keyboard) will be unnecessary. Direct control of the computer from the brain, and direct feedback to the brain. Further down, I speculate that the feedback may even stimulate the sensory centers, to the extent of providing a full sensual experience, completely virtually.

In this paradigm, the body is seen only as a vehicle of geting pleasure, and if pleasure can be directly and instantly delivered to the brain, why bother with physical acts? Why bother getting up from the couch?

More and more, I think, we will see pleasures (and ads, which support them) being more precisely targeted.

Physical health is obviously going to suffer, but are there any other consequences?

I think, firstly, digital entertainment is going to result in intellectual devolution for a vast majority of people. Some will use the new tools to further their understanding, but most will use these to augment their existing biases.

Digital entertainment puts one in control. Whether it be a click of the mouse, or pressing a button to change a channel on the TV, one is enabled to be more and more impatient, selective, and intolerant. Since now one has the power to not perceive what one does not want to, what happens to intellectual growth? There is no incentive (or lack of choice) to watch something which one may not agree with. And disagreement, criticism of one's ideas, and dialectical engagement is the essential ingredient of intellectual growth.

Secondly, facts take a backseat, and perceptions and impressions and opinions become primary. After all, if one's primary interface to the world is through a screen, what is the difference between a war shown in a movie, and a war shown as a news item?

Thirdly, the democratic process is undermined. What is the value of an opinion, if it is based on what you have been told? Driven by what is most visible in the digital world (controlled by media houses), and given that it is too much effort to find out what is really true in a flood of information, most people are going to end up believing what big media needs them to believe.

Fourthly, actual relationships (if any) will get burdened from the stress of conforming to virtual idealizations. What was earlier a teenage fantasy (the Mills and Boon romances) is now an adult expectation, due to the larger and larger role media and its depictions of relationships (and physical beauty, and sex) are playing in our lives.

There are many more consequences, but these derive from the above.

...

Do you have a choice of disengaging from the virtual/digital world and still not feel lonely, isolated, without anyone to share your experiences with? What if most of your relatives, friends, colleagues are deep in the "matrix"? Will you be able to coax them out? Isn't it true that these days, people resent you if you take them away from their phone, computer or television? What will you do without using the very tools of communication that others are hooked on to?

It is a tough problem, and is going to become much tougher. What are your thoughts on this new world, where with your minds and souls being nourished through wires, your body is only useful as a provider of blood sugar to your brain?

Is the day far when education will be primarily how to learn to use a computer, work will be primarily how to instruct a computer and to create digital content, and entertainment will be primarily hooking on to the computer?

Look around.

Sunday, December 20, 2009

On Being Touchy

Incident A:

Hundreds respond with outrage and vehemence at the ill-worded and hence misunderstood (but not ill-intended, as later clarified by the company spokesperson) publicity stunt by the international ice-cream vendor Haagen-Dazs.

Incident B:

Lawrence Summers hounded out of Harvard University because of a statement commenting on whether some intellectual differences between men and women were inherent or due to socialization.

And the following remarkable passages from Industrial Society and Its Future by Theodore Kaczynski:

Hundreds respond with outrage and vehemence at the ill-worded and hence misunderstood (but not ill-intended, as later clarified by the company spokesperson) publicity stunt by the international ice-cream vendor Haagen-Dazs.

Incident B:

Lawrence Summers hounded out of Harvard University because of a statement commenting on whether some intellectual differences between men and women were inherent or due to socialization.

And the following remarkable passages from Industrial Society and Its Future by Theodore Kaczynski:

11. When someone interprets as derogatory almost anything that is said about him (or about groups with whom he identifies) we conclude that he has inferiority feelings or low self-esteem. This tendency is pronounced among minority rights advocates, whether or not they belong to the minority groups whose rights they defend. They are hypersensitive about the words used to designate minorities. The terms "negro," "oriental," "handicapped" or "chick" for an African, an Asian, a disabled person or a woman originally had no derogatory connotation. "Broad" and "chick" were merely the feminine equivalents of "guy," "dude" or "fellow." The negative connotations have been attached to these terms by the activists themselves. Some animal rights advocates have gone so far as to reject the word "pet" and insist on its replacement by "animal companion." Leftist anthropologists go to great lengths to avoid saying anything about primitive peoples that could conceivably be interpreted as negative. They want to replace the word "primitive" by "nonliterate." They seem almost paranoid about anything that might suggest that any primitive culture is inferior to our own. (We do not mean to imply that primitive cultures ARE inferior to ours. We merely point out the hypersensitivity of leftish anthropologists.)

...

14. Feminists are desperately anxious to prove that women are as strong as capable as men. Clearly they are nagged by a fear that women may NOT be as strong and as capable as men.

Wednesday, December 16, 2009

Rocket Singh by Shimit Amin

Hmmm, where to start? At the end, I guess!

This film, like Ramanand Sagar's Ramayana (a vignette of which is shown about halfway through the film), is ultimately a moral tale. Yes, the end too nicely wraps the film up. Yes, the ending is convenient. Yes, the change-of-heart of the "villain" is too sudden. But, given the fact that this is a film with a message (more on that below), I found the ending reasonable.

Rocket Singh is the coming of age story of an honest man who does not easily give in to the ways of the world. He tries to do the right thing and he fails (is not effective at his job), succeeds (starts his own venture), FAILS (gets a rude dose of reality which destroys his venture) and SUCCEEDS (all is well, all are happy, nobody yell! music peppy!).

The second FAILURE is an important failure in this film, and that is what makes this film different from other, similar, moral tales. The overriding message is obviously that corruption doesn't pay in the long term. But the subtler message seems to be that it is a bad idea even in the short term. That while pursuing the right end, right means are also important. AYS Corporation is a corrupt company, and its owner, certainly so. But that doesn't give Rocket Singh the justification to take an unapproved loan from him.

I think what the film is trying to say is: There are bad rules (the rules of the game) and the good rules (the rule of law). The first category of rules are pooh-poohed, but the second set of rules are upheld as important. And in my view, the film is sensible in doing so. After the fiasco, one of Rocket Singh's partners in his illegal venture, his immediate boss Nitin, is shown dejectedly applying for a new job while his worried wife and his kids look on. There is only a hint of the legal machinery in the police station, but it is enough for the purposes of the film that the machinery is shown to work as intended.

Even the complaint that Rocket Singh makes against a corrupt client is shown to have had at least some effect. Hence, the film is trying to say, this is not after all a world where just because you are right you can take unlimited liberties, or that just because the world is corrupt you will face no consequences.

The film starts with some extremely well-framed compositions of the common objects in a middle class North Indian home. This was one of the rare films in which a Sikh character is not a caricature but is depicted as a normal human being. Prem Chopra was a pleasant delight to behold as the elderly Papaji (or was it Dadaji) of Rocket Singh.

The screenplay is taut, with nary a scene that drags. The dialogue is excellent, in fact. The pervert sys-admin provides the lion's share of laugh-aloud moments. His lecherous though infantile character is extremely well-done. This is also one of the few mainstream Bollywood films which does not shy away from closing up on a character's face. It is a pleasure to enjoy the uniformly good acting and the facial expressions of the characters.

As a conscious choice, the director does not dive deep into a romantic sub-plot. And the film is better for it.

This film, like Ramanand Sagar's Ramayana (a vignette of which is shown about halfway through the film), is ultimately a moral tale. Yes, the end too nicely wraps the film up. Yes, the ending is convenient. Yes, the change-of-heart of the "villain" is too sudden. But, given the fact that this is a film with a message (more on that below), I found the ending reasonable.

Rocket Singh is the coming of age story of an honest man who does not easily give in to the ways of the world. He tries to do the right thing and he fails (is not effective at his job), succeeds (starts his own venture), FAILS (gets a rude dose of reality which destroys his venture) and SUCCEEDS (all is well, all are happy, nobody yell! music peppy!).

The second FAILURE is an important failure in this film, and that is what makes this film different from other, similar, moral tales. The overriding message is obviously that corruption doesn't pay in the long term. But the subtler message seems to be that it is a bad idea even in the short term. That while pursuing the right end, right means are also important. AYS Corporation is a corrupt company, and its owner, certainly so. But that doesn't give Rocket Singh the justification to take an unapproved loan from him.

I think what the film is trying to say is: There are bad rules (the rules of the game) and the good rules (the rule of law). The first category of rules are pooh-poohed, but the second set of rules are upheld as important. And in my view, the film is sensible in doing so. After the fiasco, one of Rocket Singh's partners in his illegal venture, his immediate boss Nitin, is shown dejectedly applying for a new job while his worried wife and his kids look on. There is only a hint of the legal machinery in the police station, but it is enough for the purposes of the film that the machinery is shown to work as intended.

Even the complaint that Rocket Singh makes against a corrupt client is shown to have had at least some effect. Hence, the film is trying to say, this is not after all a world where just because you are right you can take unlimited liberties, or that just because the world is corrupt you will face no consequences.

The film starts with some extremely well-framed compositions of the common objects in a middle class North Indian home. This was one of the rare films in which a Sikh character is not a caricature but is depicted as a normal human being. Prem Chopra was a pleasant delight to behold as the elderly Papaji (or was it Dadaji) of Rocket Singh.

The screenplay is taut, with nary a scene that drags. The dialogue is excellent, in fact. The pervert sys-admin provides the lion's share of laugh-aloud moments. His lecherous though infantile character is extremely well-done. This is also one of the few mainstream Bollywood films which does not shy away from closing up on a character's face. It is a pleasure to enjoy the uniformly good acting and the facial expressions of the characters.

As a conscious choice, the director does not dive deep into a romantic sub-plot. And the film is better for it.

Friday, December 11, 2009

Films Seen Recently

Transsiberian (Brad Anderson, 2008): A curious crime drama where the viewers know more than any single character, and wherefore, the film is less of a whodunnit than a study of how a rather implausible crime and further implausible events are mishandled by the culprit. As in many such films, the deus ex machina denouement is absurd.

Happy Go-Lucky (Mike Leigh, 2008): This was my second viewing. Some notes about Poppy: ... However, even if she is at times irritating, it is striking to note that she is an energy provider, and not someone who needs constant bucking up (and hence not an energy sink). So even though her "giving" is ill-advised at times (when others are not receptive, e.g.), it is generally quite harmless. Many others in the film are so wounded inside that they end up burdening others with their sorrow, anguish and general pessimism. Hence, I consider the "burden" she puts on others by almost pushing them to share in her cheerfulness as a happier alternative than to remain aloof, or to burden others by one's sullenness or sour mood.

Of course, if she was more aware, she would modulate her "pushing" as per the situation (when in the film it is almost a monotonically exuberant cheerfulness). It is as if she is a compulsive cheerio (and since the root is compulsion, or her nature, it is not a matter of choice which others can then emulate). And being a compulsive cheerio, she does exacerbate certain situations (e.g. with Scott) in which a calm silence could have been better.

District 9 (Neill Blomkamp, 2009): Interesting take on human rights and on class warfare, shallow characters and video-game-weaponry mar this otherwise interesting and uncharacteristically misanthropic film.

Lakeview Terrace (Neil LaBute, 2008): I saw this film after it was highly recommended by a favorite reviewer. Social misfits are interesting character studies. The film is a curious take on race relations in the United States. I also recommend The House of Sand and Fog (Vadim Perelman, 2003) for those who like this film.

Sexy Beast (Jonathan Glazer, 2000): Ben Kingsley as a psychopathic gangster in a remarkable, bravura performance. In a flawless white shirt. The starting and the ending of the film are cute and atmospheric.

Inglourious Basterds (Quentin Tarantino, 2009): An exercise in signature-style, film references and award hunger, the film is notable (as far as I am concerned) only for the strong and memorable performance by Christoph Waltz. The scenes drag on for too long at times, while some reviewers see that as the point. Mr Tarantino never has much to say, but revels in his formal ability to say that little. And his formal ability mostly consists in long takes and inane dialogue. Unimpressed.

Doubt (John Patrick Shanley, 2008): The film looks good, the actors do their jobs rather well (especially Ms Streep and Ms Davis), but the film is quite flat in tone, and the characters are not deep enough for one to care about them. It pans like a story, not a real occurence. Which is perhaps because, after all, it is a literary adaptation.

Happy Go-Lucky (Mike Leigh, 2008): This was my second viewing. Some notes about Poppy: ... However, even if she is at times irritating, it is striking to note that she is an energy provider, and not someone who needs constant bucking up (and hence not an energy sink). So even though her "giving" is ill-advised at times (when others are not receptive, e.g.), it is generally quite harmless. Many others in the film are so wounded inside that they end up burdening others with their sorrow, anguish and general pessimism. Hence, I consider the "burden" she puts on others by almost pushing them to share in her cheerfulness as a happier alternative than to remain aloof, or to burden others by one's sullenness or sour mood.

Of course, if she was more aware, she would modulate her "pushing" as per the situation (when in the film it is almost a monotonically exuberant cheerfulness). It is as if she is a compulsive cheerio (and since the root is compulsion, or her nature, it is not a matter of choice which others can then emulate). And being a compulsive cheerio, she does exacerbate certain situations (e.g. with Scott) in which a calm silence could have been better.

District 9 (Neill Blomkamp, 2009): Interesting take on human rights and on class warfare, shallow characters and video-game-weaponry mar this otherwise interesting and uncharacteristically misanthropic film.

Lakeview Terrace (Neil LaBute, 2008): I saw this film after it was highly recommended by a favorite reviewer. Social misfits are interesting character studies. The film is a curious take on race relations in the United States. I also recommend The House of Sand and Fog (Vadim Perelman, 2003) for those who like this film.

Sexy Beast (Jonathan Glazer, 2000): Ben Kingsley as a psychopathic gangster in a remarkable, bravura performance. In a flawless white shirt. The starting and the ending of the film are cute and atmospheric.

Inglourious Basterds (Quentin Tarantino, 2009): An exercise in signature-style, film references and award hunger, the film is notable (as far as I am concerned) only for the strong and memorable performance by Christoph Waltz. The scenes drag on for too long at times, while some reviewers see that as the point. Mr Tarantino never has much to say, but revels in his formal ability to say that little. And his formal ability mostly consists in long takes and inane dialogue. Unimpressed.

Doubt (John Patrick Shanley, 2008): The film looks good, the actors do their jobs rather well (especially Ms Streep and Ms Davis), but the film is quite flat in tone, and the characters are not deep enough for one to care about them. It pans like a story, not a real occurence. Which is perhaps because, after all, it is a literary adaptation.

Monday, November 09, 2009

On Analyses of Sport Events

I realize that sporting events such as international cricket matches and World Boxing Championships are entertaining because they are exciting, tribal, channels of aggression and adrenaline, etc., and I do not begrudge those who seem to find unending delight in watching these events and cheering for their favorite teams.

However, what I do find quite amusing is the "analysis" of a win or a loss in terms of statistics, "weather conditions", "team morale". As a typical example of this ludicrous post-facto wisdom, read this. (notice the word which is part of the URL).

In short, teams lose because they do not perform well (!). That otherwise intelligent people fall for such analyses simply boggles the mind.

However, what I do find quite amusing is the "analysis" of a win or a loss in terms of statistics, "weather conditions", "team morale". As a typical example of this ludicrous post-facto wisdom, read this. (notice the word which is part of the URL).

In short, teams lose because they do not perform well (!). That otherwise intelligent people fall for such analyses simply boggles the mind.

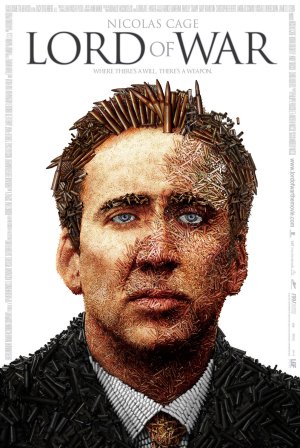

The Pacifist and the Warlord

- Lord of War (Andrew Niccol, 2005): Nicolas Cage acts as an illegal gunrunner, and this film is a nihilistic look at humans' propensity for violence. Not at all preachy, dripping with irony and black humour (some of which may be found repulsive by compassionate souls), and with some stunning cinematography, the film is not a glorification of Mr Cage's character, but is rather a perplexing treatise on harm and malice. The gunrunner is not malicious at all, but he is engaged in helping others carry out their malice. "I don't want people dead, Agent Valentine. I don't put a gun to anybody's head and make them shoot. But shooting is better for business. But, I prefer people to fire my guns and miss." And further, in a wry moment, he remarks: "They say 'Evil prevails when good men fail to act.' What they ought to say is, 'Evil prevails.'"

- The Mission (Roland Joffé, 1986): A completely different kind of film from the above: serious, sincere, poetic, a polemic against violence. Father Gabriel (Jeremy Irons, in a standout performance) is a Jesuit priest in opposition to the colonial powers in 18th century South America. He refuses to resist the violent aggressors, and leads his mission to martyrdom. One wonders at the end if his attachment to pacifism was also in part responsible for the horrific violence to the people under his leadership. One also wonders if peace and love can ever be taught without recourse to divinity. Very often, the religious claptrap is justified because it serves ostensibly noble ends. The film is rightly cherished for its great scenery and lilting music and won the Golden Palm at Cannes. (And it is rather peculiar that a film about the horrors of violent aggression shows a warrior on its poster, rather than, say, a face expressing love and kindness)

Tuesday, November 03, 2009

Antichrist by Lars von Trier

A film not for the faint of heart, or for the weak of mind for that matter (I plead guilty to the charge of Elitism). The film is not just extremely violent, it also raises serious questions about the war of the sexes, about rationality versus nature debate, about religion, and about the nurture instinct versus the desire instinct.

Starting almost operatically, with a very high degree of cinematic control, the film plunges slowly, chapter by chapter, into the dark recesses and chaos of a woman's uncontrollable nature.

There are distinct (if inadvertent) echoes of Irreversible (Gaspar Noe, 2002), especially as it explores the issue of whether female nature inspires violence (in both films, the woman is subjected to horrific violence), the nature of desire and domination (in both films, the woman is a very wilful character till the very end who dominates the man/men emotionally till she is avenged physically by mankind), the drives of sadism (in both films, hurtful violence is part of sexuality), grief and madness, and the treatment of woman as nature (in both films, there is a spectacular shot of the woman being an inseparable part of the green of nature).

I think the film raises serious issues, but I also appreciate Mike D'Angelo when he writes in his open letter to von Trier:

Nature is not just the trees and the birds, it is also our own impulses and passions. The force of passions scare Her, and (in the pyramid of her fears) her deepest fear is therefore depicted as that of Her own Self. I have to say that I was bemused by the overt symbolism of bondage (a round stone, no less, tied (sic) to the man's leg by the woman). For those who want to explore the nature of self-injury as a form of revenge against one's own sexuality, and who (WARNING) do not flinch easily, I recommend Cutting Moments (Douglas Buck, 1997), a rather disturbing short film.

I find the following comment on IMDB to be very insightful about this film (Warning: SPOILERS):

Starting almost operatically, with a very high degree of cinematic control, the film plunges slowly, chapter by chapter, into the dark recesses and chaos of a woman's uncontrollable nature.

There are distinct (if inadvertent) echoes of Irreversible (Gaspar Noe, 2002), especially as it explores the issue of whether female nature inspires violence (in both films, the woman is subjected to horrific violence), the nature of desire and domination (in both films, the woman is a very wilful character till the very end who dominates the man/men emotionally till she is avenged physically by mankind), the drives of sadism (in both films, hurtful violence is part of sexuality), grief and madness, and the treatment of woman as nature (in both films, there is a spectacular shot of the woman being an inseparable part of the green of nature).

I think the film raises serious issues, but I also appreciate Mike D'Angelo when he writes in his open letter to von Trier:

I think you’re in deadly earnest about the nature of grief and its relation to madness. And yet you take it so far over the top, in so many different ways, that it’s almost impossible not to laugh.To be fair to von Trier and to the film, I didn't laugh even once. I found the film quite somber and meaningful, but I do agree that some of the scenes might be too much for a normal viewer. von Trier strays as far from his Dogme-95 manifesto as possible: using slow motion, tricks of lighting, rotoscoping, special effects, background music, ... What hasn't changed is the extreme demands he places on his actors. The performance by Charlotte Gainsbourg stands out in my limited film experience as one of the finest and most harrowing performances by an actress. Her final scene with her husband is nothing short of extraordinary.

Nature is not just the trees and the birds, it is also our own impulses and passions. The force of passions scare Her, and (in the pyramid of her fears) her deepest fear is therefore depicted as that of Her own Self. I have to say that I was bemused by the overt symbolism of bondage (a round stone, no less, tied (sic) to the man's leg by the woman). For those who want to explore the nature of self-injury as a form of revenge against one's own sexuality, and who (WARNING) do not flinch easily, I recommend Cutting Moments (Douglas Buck, 1997), a rather disturbing short film.

I find the following comment on IMDB to be very insightful about this film (Warning: SPOILERS):

In the film, “She” — the name of Gainsborg’s character — had been writing a thesis on violence against women through history. She realized that “nature … causes people to do evil things to women,” but concluded that female nature is also part of this cycle; the nature of women inspires violence. As She explains it, women lack complete control over their own bodies, which are animated by satanic spirit.

For her, images such as those she collects of early modern witches copulating with demons, capture an essential truth. Her therapist husband, whose relentless rationalism fails to cure her, resists the inevitability of this truth until the very end.

Gainsbourg’s character, through her sexual frenzies and shifts of mood, seems connected to the natural world of Eden around her. When she observes that “Nature is Satan’s church,” it is not difficult to infer that while Christ was half man, half divine, Antichrist is half woman, half Satanic. Indeed, She does not seem completely in control of herself. Fearing his abandonment, She suddenly brutalizes her husband's genitalia by smashing it with a huge log of wood. Then she just as suddenly switches back to nurturing mode, by her sudden frenzied manual stimulation of his traumatized penis to orgasm. In her brutalizing mode, for example, She bolts a grindstone to his leg, and then throws the wrench under the house to prevent an escape. Later, in her nurturing mode, She wants to remove the grindstone and help her husband back to the house; She looks for the wrench in the toolbox as if she were not aware that she herself had hidden it elsewhere.

Such splitting of her personality recurs. In one (notorious) sequence, She remembers watching her child fall from the window while she did nothing to stop him because she was caught up in sexual ecstasy. When, horrified at her own conduct, She performs a genital self-mutilation, she is trying to protect herself as well as others from this uncontrollable destructive force within herself.

The fact that She herself is horrified by female sexual power seems to undermine any notion that what the film depicts is a result of patriarchal oppression. Rather, it is hard to escape the conclusion that She has rediscovered the truth that He, in his rationalistic naivete, has dismissed out of hand. And their own and the world's

expulsion from Eden — the corruption of the world — was not simply the Fall of Man but the Rise of Woman.

Thursday, October 29, 2009

The Provocation of the Ego

In interacting with people, how important is it to take cognizance of their egos and their attachments? Is consideration of another's feelings a pandering tactic and a form of manipulation? Or can it be helpful to lessen unnecessary friction?

What do you think? After all this is a slippery slope where one can indulge in manipulation and justify it as saving others from themselves? Spiritual teachers, in particular, are fond of being disingenuous, mystifying, distant, acting as veneration-worthy towards their disciples "for their own good".

Also, it is quite dangerous to presume to know what is good for the other. Is it acceptable to assume, at least in some cases, what is in another's best interests? In those cases, is manipulation justified?

I think that in general, provoking someone's ego and self-defense is counter-productive. The best conversationalists are those who can communicate in a way which does not raise others' defenses needlessly. It is, in my opinion, important to be wary of what can flare up another's tempers and ego and leave him not just where he was or worse, but also distant and angry with the one who is trying to communicate, and so closing the possibilities of further engagement.

However, since ego, temper, passions are what I consider the source of human suffering, how useful is it to sidestep them in order to apply a therapeutic balm? Will it not postpone another's freedom? Is it not more important to point out what is causing the problem, rather than to address it in a temporary way?

The balance that I strike is this: I take care not to provoke people at all when dealing with them functionally (i.e. when my association with them is mandated by circumstances). But between friends, those interested in the human condition, with people who have chosen to associate with me, I assume that they will not be offended no matter what I say.

However, it gets tricky with people who are neither very close, nor entirely functional in one's association with them. In such cases, it is best (I think) to start tentatively, and if the person shows gusto and a non-offending attitude, to amp up the mutual enquiry and questioning. Otherwise, to back off. To try to "do good" to everybody despite their reluctance, is, I think a tad compulsive.

Again, what do you think?

What do you think? After all this is a slippery slope where one can indulge in manipulation and justify it as saving others from themselves? Spiritual teachers, in particular, are fond of being disingenuous, mystifying, distant, acting as veneration-worthy towards their disciples "for their own good".

Also, it is quite dangerous to presume to know what is good for the other. Is it acceptable to assume, at least in some cases, what is in another's best interests? In those cases, is manipulation justified?

I think that in general, provoking someone's ego and self-defense is counter-productive. The best conversationalists are those who can communicate in a way which does not raise others' defenses needlessly. It is, in my opinion, important to be wary of what can flare up another's tempers and ego and leave him not just where he was or worse, but also distant and angry with the one who is trying to communicate, and so closing the possibilities of further engagement.

However, since ego, temper, passions are what I consider the source of human suffering, how useful is it to sidestep them in order to apply a therapeutic balm? Will it not postpone another's freedom? Is it not more important to point out what is causing the problem, rather than to address it in a temporary way?

The balance that I strike is this: I take care not to provoke people at all when dealing with them functionally (i.e. when my association with them is mandated by circumstances). But between friends, those interested in the human condition, with people who have chosen to associate with me, I assume that they will not be offended no matter what I say.

However, it gets tricky with people who are neither very close, nor entirely functional in one's association with them. In such cases, it is best (I think) to start tentatively, and if the person shows gusto and a non-offending attitude, to amp up the mutual enquiry and questioning. Otherwise, to back off. To try to "do good" to everybody despite their reluctance, is, I think a tad compulsive.

Again, what do you think?

The Burden of Memory

When I was young, whenever I used to come across a news of someone committing suicide, I was perplexed as to why that person did not simply start a new life somewhere else. I considered such people, e.g. a farmer committing suicide due to an unpayable loan, a lover unable to unite with his beloved, as ones who were limiting their options. Life is too vast, I thought, and why end it if one is frustrated in one environment? Why not start over?

Only much later, I realized why not. It may seem trite, but it took me quite a while to experience it myself and thus realize the force of the factor involved.

The invisible threads and burdens of emotional memories bind us wherever we go. One may leave one's family and one's home, one may start a new life elsewhere, but what is to be done about the scars of heart and of emotional ties? Thus, a lover is unable to imagine a life without his beloved. In his valid reckoning, the failed love and the ache will haunt him no matter where he goes. In the same vein, a financially ruined man validly reckons that it will be well nigh impossible for him to rebuild his self-esteem in a new place, and for him to get over the feeling that he ran away like a coward. In the grip of such thoughts, many consider suicide and hence oblivion a better choice than to live with these burdens.

That also explains that when life becomes unbearable, it is the feelings inside which are unbearable, and which are sought to be drowned in addictions, drugs, alcohol, sleep, activity, etc. When there is no avenue to live a life free from these feelings, and when these feelings make one unable to live, one starts considering suicide as a possibility.

In the film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Michel Gondry and Charlie Kaufman examine the possibility of erasing one's hurtful memories so that one may be able to live again. The film does not explore this idea fully, and becomes a tad romantic towards the end, but the idea is immensely powerful. Most of us are so scarred and burdened with our emotional history that to be able to wipe it clean would literally be a new lease of life.

Psychiatry and therapy is primarily to weed out the most persistent of our emotional knots. Mood elevating drugs is an industry in itself. Distractions take us away from ourselves.

But what if one could indeed put the burden away, oneself? Not just dissociate from the painful self and its memories, but to wipe it off? To live a clean and pure life in which not only the emotional past is wiped clean, there is no emotional present to control and no emotional future to be afraid of (or to look forward to).

In essence ... the extirpation of one's heart and soul.

Scary? Inhuman? Too extreme?

That is the promise of Actual Freedom.

Only much later, I realized why not. It may seem trite, but it took me quite a while to experience it myself and thus realize the force of the factor involved.

The invisible threads and burdens of emotional memories bind us wherever we go. One may leave one's family and one's home, one may start a new life elsewhere, but what is to be done about the scars of heart and of emotional ties? Thus, a lover is unable to imagine a life without his beloved. In his valid reckoning, the failed love and the ache will haunt him no matter where he goes. In the same vein, a financially ruined man validly reckons that it will be well nigh impossible for him to rebuild his self-esteem in a new place, and for him to get over the feeling that he ran away like a coward. In the grip of such thoughts, many consider suicide and hence oblivion a better choice than to live with these burdens.

That also explains that when life becomes unbearable, it is the feelings inside which are unbearable, and which are sought to be drowned in addictions, drugs, alcohol, sleep, activity, etc. When there is no avenue to live a life free from these feelings, and when these feelings make one unable to live, one starts considering suicide as a possibility.

In the film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Michel Gondry and Charlie Kaufman examine the possibility of erasing one's hurtful memories so that one may be able to live again. The film does not explore this idea fully, and becomes a tad romantic towards the end, but the idea is immensely powerful. Most of us are so scarred and burdened with our emotional history that to be able to wipe it clean would literally be a new lease of life.

Psychiatry and therapy is primarily to weed out the most persistent of our emotional knots. Mood elevating drugs is an industry in itself. Distractions take us away from ourselves.

But what if one could indeed put the burden away, oneself? Not just dissociate from the painful self and its memories, but to wipe it off? To live a clean and pure life in which not only the emotional past is wiped clean, there is no emotional present to control and no emotional future to be afraid of (or to look forward to).

In essence ... the extirpation of one's heart and soul.

Scary? Inhuman? Too extreme?

That is the promise of Actual Freedom.

Public Enemies by Michael Mann

I consider cinema to be both an art form as well as a medium of experience and provocation. Film lovers may differ in their appreciation of a film. Some consider the style, formal dexterity and virtuosity as more important. Others consider the message and the emotions a film can provoke to be primary. Most fall somewhere in the middle.

Public Enemies is a gangster film made by a director who is trying to further the frontiers of film art. There is nothing new, absolutely nothing about the human condition that is illustrated by this film. And moreover, if you watch this film with the expectation of an emotional involvement, you will again be sorely disappointed.

When we recently watched Au Hasard Balthazar, one of the fellow spectators found the film pretentious because, according to him, the director was merely indulging in exhibiting his formal expertise and the film did not raise any important questions. I consider this kind of viewer expectation to be valid, but to look for provocation and lessons in every event is a peculiar kind of narcissism as well.

It is important to meet a film on its own turf. To appreciate a film for what it is trying to do, rather than to be gratified when it fulfills one's expectations (even an expectation of depth), is, I think, an important milestone for a film lover.

Au Hasard Balthazar, for example, is a film about suffering, and in a way, everybody already knows that life can be tough. But Bresson is saying it in a way which is new. Like a painting, or a poem which expresses a familiar sentiment, it is therefore not important for what it depicts, but in how it depicts it.

Public Enemies could not be farther from the Bresson film in its film language. Michael Mann uses gunfire as a brush on his palette. He uses elegaic music, dark hues, operatic sounds, echoing shots in open spaces, reflection and brilliant contrasts, wide angle lenses, and so on, to create a visual feast. There is only a hint of a narrative in this film, which is one gunfight after another, and of a bunch of policemen chasing an iconic law breaker.

To meet a film like Public Enemies at its turf is to try to see what the director is trying to do, and then to judge whether he has been successful or not. In my book, formal experimentation is an admirable quality in itself, and if it works at least at some level to create something which can elicit a "Wow", it succeeds. The opening jailbreak sequence in the Michael Mann film is just one such instance which succeeds spectacularly.

This is a film which needs to be seen on a big screen with a sophisticated audio system. The themes raised by this film (the love of the outlaw, the seduction by a demonic force, the bravado of a life lived in the moment) are mundane as compared to the visual and aural artistry.

I was disappointed that Giovanni Ribisi was not given more screen time, but that is a small gripe.

Public Enemies is a gangster film made by a director who is trying to further the frontiers of film art. There is nothing new, absolutely nothing about the human condition that is illustrated by this film. And moreover, if you watch this film with the expectation of an emotional involvement, you will again be sorely disappointed.

When we recently watched Au Hasard Balthazar, one of the fellow spectators found the film pretentious because, according to him, the director was merely indulging in exhibiting his formal expertise and the film did not raise any important questions. I consider this kind of viewer expectation to be valid, but to look for provocation and lessons in every event is a peculiar kind of narcissism as well.

It is important to meet a film on its own turf. To appreciate a film for what it is trying to do, rather than to be gratified when it fulfills one's expectations (even an expectation of depth), is, I think, an important milestone for a film lover.

Au Hasard Balthazar, for example, is a film about suffering, and in a way, everybody already knows that life can be tough. But Bresson is saying it in a way which is new. Like a painting, or a poem which expresses a familiar sentiment, it is therefore not important for what it depicts, but in how it depicts it.

Public Enemies could not be farther from the Bresson film in its film language. Michael Mann uses gunfire as a brush on his palette. He uses elegaic music, dark hues, operatic sounds, echoing shots in open spaces, reflection and brilliant contrasts, wide angle lenses, and so on, to create a visual feast. There is only a hint of a narrative in this film, which is one gunfight after another, and of a bunch of policemen chasing an iconic law breaker.

To meet a film like Public Enemies at its turf is to try to see what the director is trying to do, and then to judge whether he has been successful or not. In my book, formal experimentation is an admirable quality in itself, and if it works at least at some level to create something which can elicit a "Wow", it succeeds. The opening jailbreak sequence in the Michael Mann film is just one such instance which succeeds spectacularly.

This is a film which needs to be seen on a big screen with a sophisticated audio system. The themes raised by this film (the love of the outlaw, the seduction by a demonic force, the bravado of a life lived in the moment) are mundane as compared to the visual and aural artistry.

I was disappointed that Giovanni Ribisi was not given more screen time, but that is a small gripe.

Monday, October 12, 2009

Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi by Sudhir Mishra

The film is a better-than-average reiminiscence of a particulary troubled period in modern India. While the 60s (or Sexties, as it is sometimes called) were times of experimentation in the US, in India the youth were waking up to the fact that the promise of freedom had failed, that repression continued in old and new forms. While in the US, the protests against the state were mostly non-violent and non-ambitious, in India the violent Naxalite movement aimed at nothing less than the overthrow of the state apparatus. In recent years, the Naxalite movement has lost much of its ideological high ground, but it is still a grave presence in many tribal and poorer regions of India.

The three main characters in this film differ in their dedication to "change". Siddharth is an idealist, committed to bringing about change, violently if needed. Geeta, who eulogizes and loves him, lives in his shadow. Vikram, hailing from a middle class family, rejects all this talk of "change" and works the system to become wealthy and powerful.

The film is interesting in that it traces the three characters' uncertain trajectories. None ends up in a place they had wanted in the beginning. The cost of waging a war against the organized militia of the state is brought out in sharp focus as it breaks down relationships, makes even the toughest of spirits resign in defeat, and leads to horrendous and callous violence.

Siddharth admits defeat and moves back into the mainstream. Vikram is the victim of circumstances, driven by his love of Geeta. But it is Geeta who finally finds her place in the world. She is one of the strongest women portrayed in recent Indian cinema. Self-assured, never wavering, anguished at times but still not losing hope, she emerges from a life in which she has been living in a shadow of one man after another, and is an elevating presence by the end of the film. One looks forward to more performances from this talented actress.

A rather realistic (and pessimistic) portrait of politics and the police is presented. Patronage still runs strong in modern India, and therefore it is modern only in name.

The direction is good, with attention to detail, but I am hesitant to call it flawless. I seem to feel that editing in Indian art films has actually become worse over the years. Dialogue delivery is at times forced, and gestures (especially laughter and eye movement) are frequently not well-timed.

What also jars is the profusion of English dialogue. I am not sure about the reason why Geeta is depicted as more comfortable in English (and hence the letters to her, written by Vikram and Siddharth, are in English) but not only is this a distancing choice, the accent and facial expressions of Geeta end up portraying her more as a Westerner living in India rather than an Indian girl struggling with family, society, culture. Geeta gives up her marriage almost without any trouble, has a child out of wedlock without any eyebrows being raised, and in general lives with nary a care for social customs. This was the only unrealistic part of the film. It doesn't ruin the film, but I daresay that her character is unrelatable for most Indian women. It is convenient that she is shown as having grown up abroad. A contrast to her character is that of Sujara Chatterjee in Hazaar Chaurasi ki Maa (Govind Nihalani, 1998), who struggles with a repressive family structure in addition to a repressive state.

There are numerous small characters in this film which are curious and realistic, but don't lend much to the narrative. The narrative is therefore loose. I consider one of the director's earlier films, Yeh Woh Manzil To Nahin, which I had the good fortune of catching on television in my adolescence, a much better and tightly narrated film.

The posters of this film are hugely disappointing. They are fashionable and glittering, instead of provocative. Judge for yourself.

The three main characters in this film differ in their dedication to "change". Siddharth is an idealist, committed to bringing about change, violently if needed. Geeta, who eulogizes and loves him, lives in his shadow. Vikram, hailing from a middle class family, rejects all this talk of "change" and works the system to become wealthy and powerful.

The film is interesting in that it traces the three characters' uncertain trajectories. None ends up in a place they had wanted in the beginning. The cost of waging a war against the organized militia of the state is brought out in sharp focus as it breaks down relationships, makes even the toughest of spirits resign in defeat, and leads to horrendous and callous violence.

Siddharth admits defeat and moves back into the mainstream. Vikram is the victim of circumstances, driven by his love of Geeta. But it is Geeta who finally finds her place in the world. She is one of the strongest women portrayed in recent Indian cinema. Self-assured, never wavering, anguished at times but still not losing hope, she emerges from a life in which she has been living in a shadow of one man after another, and is an elevating presence by the end of the film. One looks forward to more performances from this talented actress.

A rather realistic (and pessimistic) portrait of politics and the police is presented. Patronage still runs strong in modern India, and therefore it is modern only in name.

The direction is good, with attention to detail, but I am hesitant to call it flawless. I seem to feel that editing in Indian art films has actually become worse over the years. Dialogue delivery is at times forced, and gestures (especially laughter and eye movement) are frequently not well-timed.

What also jars is the profusion of English dialogue. I am not sure about the reason why Geeta is depicted as more comfortable in English (and hence the letters to her, written by Vikram and Siddharth, are in English) but not only is this a distancing choice, the accent and facial expressions of Geeta end up portraying her more as a Westerner living in India rather than an Indian girl struggling with family, society, culture. Geeta gives up her marriage almost without any trouble, has a child out of wedlock without any eyebrows being raised, and in general lives with nary a care for social customs. This was the only unrealistic part of the film. It doesn't ruin the film, but I daresay that her character is unrelatable for most Indian women. It is convenient that she is shown as having grown up abroad. A contrast to her character is that of Sujara Chatterjee in Hazaar Chaurasi ki Maa (Govind Nihalani, 1998), who struggles with a repressive family structure in addition to a repressive state.

There are numerous small characters in this film which are curious and realistic, but don't lend much to the narrative. The narrative is therefore loose. I consider one of the director's earlier films, Yeh Woh Manzil To Nahin, which I had the good fortune of catching on television in my adolescence, a much better and tightly narrated film.

The posters of this film are hugely disappointing. They are fashionable and glittering, instead of provocative. Judge for yourself.

Saturday, October 10, 2009

Autumn...

I live in North India, and for the past few days, the weather has become distinctly cooler and invigorating. The mornings are crisp. This is also the festive season in India. It was Dussehra a couple weeks back, Karwa Chauth is just past, and Diwali is round the corner.

There is celebration in the air, the markets are decked up, and kids especially are having a great time bursting crackers, eating sweets and are enjoying a forgiving atmosphere of noise and naughtiness.

One of the virtues in Buddhism is that of Mudita, being happy in others' joy (as opposed to being envious or cynical). There was a time, during my Vedanata years, when I used to scoff at circumstantial joys as merely escapism and distraction, but no more.

It is a pleasure to see people happy, even if their happiness derives from their passions or from the environment. Not only is happiness (in whatever form) enabling of an appreciation of being alive (as opposed to the denial of life in religion), it is also a respite for otherwise stressed human beings who spend most of their days in various kinds of struggles.

The "mundane" pleasures of eating, drinking, frolicking, enjoying the lights and sounds, shopping for new things for the house, gambling, getting dressed at one's best, and even elaborate ceremonies at temples, are welcome signs of people enjoying earthly life. Yes, it is consumptive, yes, it is polluting, yes, it is temporary, and one wishes there were more healthy ways of enjoying the festive season... But the joy on people's faces is there, and it is cynical to begrudge it.

During this time, one is filled with good wishes for all, and die-hard fogeys like me wish that instead of buying a "Season's Greetings" card, one could find a card which said "Life's Greetings".

Have a good time, ye all!

(photo courtesy http://www.flickr.com/photos/cheez/)

There is celebration in the air, the markets are decked up, and kids especially are having a great time bursting crackers, eating sweets and are enjoying a forgiving atmosphere of noise and naughtiness.

One of the virtues in Buddhism is that of Mudita, being happy in others' joy (as opposed to being envious or cynical). There was a time, during my Vedanata years, when I used to scoff at circumstantial joys as merely escapism and distraction, but no more.

It is a pleasure to see people happy, even if their happiness derives from their passions or from the environment. Not only is happiness (in whatever form) enabling of an appreciation of being alive (as opposed to the denial of life in religion), it is also a respite for otherwise stressed human beings who spend most of their days in various kinds of struggles.

The "mundane" pleasures of eating, drinking, frolicking, enjoying the lights and sounds, shopping for new things for the house, gambling, getting dressed at one's best, and even elaborate ceremonies at temples, are welcome signs of people enjoying earthly life. Yes, it is consumptive, yes, it is polluting, yes, it is temporary, and one wishes there were more healthy ways of enjoying the festive season... But the joy on people's faces is there, and it is cynical to begrudge it.

During this time, one is filled with good wishes for all, and die-hard fogeys like me wish that instead of buying a "Season's Greetings" card, one could find a card which said "Life's Greetings".

Have a good time, ye all!

(photo courtesy http://www.flickr.com/photos/cheez/)

Friday, October 09, 2009

Labor, Consumption, Alienation

In the knowledge economy, most people earn more than the subsistence level.

Most white collar workers seek an increased standard of living.

The standard is defined largely by the degree and manner of consumption.

Hence the prevailing definition of success is to constantly be in the top percentile of consumers.

Both labor and consumption are expenditures of energy, and both creates margins for the capitalists.

Labor is to help create, and consumption is to help destroy. Both feed each other.

The trick in encouraging consumption is to make it a part of one's identity, as a form of potency in an impotent world.

In the modern world, what one consumes defines oneself. One is perceived according to the costly labels one carries.

To feel powerful after having consumed is the big delusion that markets strive to sustain. To feel as if one is more alive after consumption.

One is willing to live in inhuman conditions in order to have a chance at the consumption carrot which the market dangles before one's eyes.

Consumption leaves one unfulfilled. But since larger carrots are always there, one doesn't suspect the path, only the milestones.

The prime need in a human being to be gratified (in terms of neurotransmitters) is manipulated ceaselessly by the market in both driving him to labor hard, and then to consume hard.

A man riding a powerful SUV and feeling good about it is the result of pervasive brainwashing, but it derives from a primal need in the man.

Without gratification in various ways, one feels alienated. And as more and more gratification is dependent on money and status, one is less and less capable of being self-sufficient for one's happiness.

The owners are not fulfilled as well, of course. But their thresholds of gratification are now so high that thousands of people have to work, and consume, to enable their neurotransmitter levels.

To turn the other way, from gratification and satiation towards joy and contentment, is the key, but it is extremely difficult, owing to the very early programming of a child gearing him towards "worldly" success.

Sex being the core drive, and the competition for mates becoming more fierce with the breakdown of the traditional structures, and with the competing ability determined by one's worldly success, it is biologically counter-intuitive for a person to turn the other way and seek contentment instead of success as defined by one's potential mates.

Since the cycle of alienation, work, consumption, gratification, alienation, work, consumption and gratification is unending, there is burning out, exhaustion and depression.

As the community breaks down, and institutions and markets take over, there is choice only in the degree of one's participation in the economic arena, not in the matter of it. (As in, one can only choose to disengage to a degree, not completely)

To live comfortably by one's own labor is easier than ever before, but to fulfill oneself in the circumstances one finds oneself is not necessarily easier, it may even have become harder than ever before. Fulfilment in normal human beings is a socially measured outcome.

As one disallows society to dictate one's fulfilment, one risks becoming anti-social and even more alienated, as compared to being only asocial. The drop-outs, the various kinds of addicts, and so on. Man is inherently social, and to get cut off from this society (which today encourages alienation) is in itself alienating.

What is the way out? I'm not entirely sure, but what I am practicing is: To question one's biological and social goals, and to risk meaninglessness, and then to come upon contentment in which there is an inherent significance to living and experiencing, and not an imposed one on the content of one's experiencing.

Most white collar workers seek an increased standard of living.

The standard is defined largely by the degree and manner of consumption.

Hence the prevailing definition of success is to constantly be in the top percentile of consumers.

Both labor and consumption are expenditures of energy, and both creates margins for the capitalists.

Labor is to help create, and consumption is to help destroy. Both feed each other.

The trick in encouraging consumption is to make it a part of one's identity, as a form of potency in an impotent world.

In the modern world, what one consumes defines oneself. One is perceived according to the costly labels one carries.

To feel powerful after having consumed is the big delusion that markets strive to sustain. To feel as if one is more alive after consumption.

One is willing to live in inhuman conditions in order to have a chance at the consumption carrot which the market dangles before one's eyes.

Consumption leaves one unfulfilled. But since larger carrots are always there, one doesn't suspect the path, only the milestones.

The prime need in a human being to be gratified (in terms of neurotransmitters) is manipulated ceaselessly by the market in both driving him to labor hard, and then to consume hard.

A man riding a powerful SUV and feeling good about it is the result of pervasive brainwashing, but it derives from a primal need in the man.

Without gratification in various ways, one feels alienated. And as more and more gratification is dependent on money and status, one is less and less capable of being self-sufficient for one's happiness.

The owners are not fulfilled as well, of course. But their thresholds of gratification are now so high that thousands of people have to work, and consume, to enable their neurotransmitter levels.

To turn the other way, from gratification and satiation towards joy and contentment, is the key, but it is extremely difficult, owing to the very early programming of a child gearing him towards "worldly" success.

Sex being the core drive, and the competition for mates becoming more fierce with the breakdown of the traditional structures, and with the competing ability determined by one's worldly success, it is biologically counter-intuitive for a person to turn the other way and seek contentment instead of success as defined by one's potential mates.

Since the cycle of alienation, work, consumption, gratification, alienation, work, consumption and gratification is unending, there is burning out, exhaustion and depression.

As the community breaks down, and institutions and markets take over, there is choice only in the degree of one's participation in the economic arena, not in the matter of it. (As in, one can only choose to disengage to a degree, not completely)

To live comfortably by one's own labor is easier than ever before, but to fulfill oneself in the circumstances one finds oneself is not necessarily easier, it may even have become harder than ever before. Fulfilment in normal human beings is a socially measured outcome.

As one disallows society to dictate one's fulfilment, one risks becoming anti-social and even more alienated, as compared to being only asocial. The drop-outs, the various kinds of addicts, and so on. Man is inherently social, and to get cut off from this society (which today encourages alienation) is in itself alienating.

What is the way out? I'm not entirely sure, but what I am practicing is: To question one's biological and social goals, and to risk meaninglessness, and then to come upon contentment in which there is an inherent significance to living and experiencing, and not an imposed one on the content of one's experiencing.

Tuesday, October 06, 2009

On Responsibility and Indifference

This post was triggered by reading about J R Oppenheimer's reaction at the successful detonation of a trial atomb bomb, a little prior to bombing of Hiroshima:

To put his reaction in perspective, the bombs killed as many as 140,000 people in Hiroshima alone.

In this case, I am willing to grant he did not have any malice towards the thousands of innocent people in Hiroshima. He was just doing his job. Neither can it be said that he was unaware of the destruction the bomb was going to cause. Hence it is neither malice, nor ignorance. But this was an extremely violent act.

The bombing was a pressure tactic to force Japan to adhere to the terms of surrender.

To be sure, most of us are not directly engaged in destructive acts. However, we are ignorant of the long-term or otherwise distant implications of our acts (on ourselves, as well as on others and on our environment), as is amply borne out by psychological neuroses and environmental pollution. A measure of obliviousness seems to be essential if one is to enjoy the fruits of civilized society.

To what extent is an individual responsible for the consequences of acts in which he acts as a conduit, or a participant? What are your reactions and thoughts on this?

Is absence of malice enough?

(A related earlier post)

Dr. Oppenheimer, on whom had rested a very heavy burden, grew tenser as the last seconds ticked off. He scarcely breathed. He held on to a post to steady himself. For the last few seconds, he stared directly ahead and then when the announcer shouted "Now!" and there came this tremendous burst of light followed shortly thereafter by the deep growling roar of the explosion, his face relaxed into an expression of tremendous relief

To put his reaction in perspective, the bombs killed as many as 140,000 people in Hiroshima alone.

In this case, I am willing to grant he did not have any malice towards the thousands of innocent people in Hiroshima. He was just doing his job. Neither can it be said that he was unaware of the destruction the bomb was going to cause. Hence it is neither malice, nor ignorance. But this was an extremely violent act.

The bombing was a pressure tactic to force Japan to adhere to the terms of surrender.

To be sure, most of us are not directly engaged in destructive acts. However, we are ignorant of the long-term or otherwise distant implications of our acts (on ourselves, as well as on others and on our environment), as is amply borne out by psychological neuroses and environmental pollution. A measure of obliviousness seems to be essential if one is to enjoy the fruits of civilized society.

To what extent is an individual responsible for the consequences of acts in which he acts as a conduit, or a participant? What are your reactions and thoughts on this?

Is absence of malice enough?

(A related earlier post)

Au Hasard Balthazar by Robert Bresson

Robert Bresson's precision in cinema is akin to J M Coetzee's precision in literature. Both share a bleak view of humanity, tempered only by a fleeting hope of individual redemption.

This was my third viewing of this remarkable film. The premise of the film is daring and simple: A donkey and a girl go through life, suffering abuse at the hands of those who have dominion over them. Whereas the donkey (Balthazar) has no choice in what path it takes, the girl (Marie) has little to choose from.

Rife with Biblical symbolism, this film is like a jewel polished to perfection. No image or sound is wasted, no frivolous words are spoken. This is a film in which the narrative is stripped to its bare essentials. Episodic and elliptical in style, the film can perhaps be best summed up in the phrase "Suffering in Silence".

There are films which do not make an overt claim of an absence of a higher power, but which illustrate it. The problem of suffering has long since been advanced as a proof that there is no God, that man is perhaps a higher animal, but an animal nevertheless who deludes himself into creating a benevolent and all-powerful God in his own image.

Many think of their childhoods wistfully and with nostalgia. The happiness during childhood is mostly the happiness of a sheltered existence and an innocence which is more ignorance and underdevelopment than uncorruptedness. In this film, both Balthazar and Marie have their happiest moments in their childhood, while in their later lives, it is one sorrow after another. A child cries not at life, nor at fate, but at something immediate which is achievable. The tears of an adult are deeper because one knows that there is no easy solution. Sorrow is an adult emotion.

The film is a highly compressed portrait of life's miseries. Godard famously called this film "the world in 90 minutes". The misery of social obligations, of adhereing to institutions and their procedures, of participating in a capitalist society, of the dubious promise of love and affection, of the unsatisfactory nature of religious solutions, of contradictory impulses within human beings, of a death without redemption.

An expert user of the Kuleshov Effect, Robert Bresson drains all emotion from faces and from eyes of his models, and demands a very different kind of viewing. This is non-consumptive cinema at its best. One has to actively participate, guess at what the characters must be thinking and feeling, speculate at what the director wants to portray. No explanations are provided, but there is a vision at work. It is not a stainless mirror, into which one can project anything. There is something which is being shown, but it is shown in a way which is neither implicit nor explicit, but which requires interpretation.

This is a hard film to watch if you understand it. And a hard film to watch if you don't. One will be silenced in the former case, and bored in the latter.

Bresson was also a master of atmospheric sound, and of highly surgical framing. His frames are sometimes perceived as incomplete, with only parts of a body or parts of a scene visible, but that very excision makes us focus on what is shown, and what isn't. It is a device to make us imagine more than we see. This film is therefore not just narratively elliptical (not every sequence is temporally or spatially linked to the one prior), but also visually incomplete. Both in the frame itself, and beyond it, one has to imagine what is left undepicted.